Notes on a walk from Dumbarton to Santiago de Compostela

But what did they hope to find, these lonely uncontrolled people, on their pointless criss-crossing journeys across rivers and mountains and city streets?

- Suhayl Saadi, Joseph's Box

Toute marche est spirituelle

- Xavier Grall

No hay camino, se hace camino al andar

- Antonio Machado

Note: (CSJ = Confraternity of St James)

For some time - about five years - I had fantasised of the possibility of walking from home to Santiago de Compostela in Spain. During the course of 2006 it became clear that the company I worked for was in serious difficulty. Feeling I had nothing much to lose I resigned my job, sold my house and set out.

Below are some notes on the less-travelled part of the path - the walk through the Scottish Borders, England, Brittany, west and south-west France.

Part of the pleasure of these journeys is to make your own plan, but if you want to see my detailed itinerary it's here.

Britain

I camped wherever possible. In England this was limited by the shortage of campsites and the extremely inclement weather of July 2007. I had frequent resort to B&B and hotels, making this part of the walk very expensive.

Start and finish

The route from Glasgow to the English border follows the Forth & Clyde canal to Falkirk, then the Union Canal to Broxburn. Leaving the canal there is a brief urban section before crossing the hills (Cauldstane Slap) to West Linton. There is an old drove road to Peebles, and thereafter you can follow the Southern Upland Way until it intersects St Cuthbert’s Way, then follow that to the top of the Pennine Way.

Walks in England are poorly waymarked, with the honourable exception of the Heart of England Way, which I loved. The paths could probably still be followed if you had a 1:25000 map, but it isn’t practical to carry all those you would need, let alone meet the costs involved. The OS 1:50000 maps are adequate for most purposes, but do not show field boundaries. As English hedges are quite impenetrable you cannot substitute a compass bearing for a lost footpath – you must find the path in order to get the breaks in the hedges and the footbridges over streams. The alternative is to plan your own route using minor roads - an option I made much use of.

Woods near Chipping Camden

On the Pennine Way I avoided most of the climbs by taking minor roads and riverside trails. This also gives a prettier walk through the dales – the tops of the Pennine Way are dull peat hag. The Pennine Way waymarking is near non-existent, so I followed it only where it was easy or there was no sensible alternative. Having damned it a little, I should say in fairness that some parts are very pretty.

After the Pennine Way one follows canals and other ‘ways’ – look at European Route 2 (E2) here. You can go to Dover and work out a way of your own to Paris, thereafter there is a Rando guide to the Spanish border. I walked to Plymouth and took the ferry to Roscoff, as there is a Rando guide from St Pol de Leon near Roscoff.

France

Distance stone, Vendée

425 leagues to Santiago!

Three guides are needed for the walk through France: the Rando (French language) series guides for Brittany and the Voie de Tours, and a short guide to the Vendée [PDF], the missing link between these two. I also used the Rando guide for Spain – by the time you get to St Jean Pied de Port your French will be pretty good!

To get from the ferry at Roscoff to St Pol de Leon it’s a couple of hours’ walk following cycle route V7 which you hit immediately on leaving the ferry terminal. The coastal path suggested by CSJ doesn’t run continuously all the way to St Pol, requiring much stumbling along a stony beach – not recommended if you have a pack on your back, and if you’ve just disembarked from the morning ferry you will also be in darkness.

The Rando guides are essential as they carry accommodation information and telephone numbers - you frequently need to phone and book ahead. A mobile phone is essential. In France phone numbers are given in pairs, so that 21364481 would be spoken as twenty-one, thirty-six, forty-four, eighty-one (in French, of course). When you book a gîte or chambre d’hôte ahead you may be asked for your mobile number as a reference, so make sure you can recite it in this form. It’s also useful to practise spelling out your name using the French pronunciation of letters of the alphabet. My name is long and difficult for French people, so I usually adopted a nom de chemin – Mr Smith – when making reservations, and made my explanations on arrival. If you have a long or unusual surname you might consider the same idea.

Nantes-Brest Canal near Guenrouet

Regarding the French language, you need to be fairly confident. My French education was the Scottish Higher course oh, a thousand years ago, but that and a refresh from the Michel Thomas CDs was enough to get me through and make me sociable in the evenings. You do need to speak the language as you are on a predominantly rural walk – a man ploughing a field in Armorica has no more need of conversational English than his counterpart in Kintyre has for French, and those are the people you will be meeting. In the entire journey through France I met only two or three people whose English was better than my French, and my French, as I’ve said, is no great shakes.

The Brittany guide is a bit, er, idiosyncratic. It gets ‘right’ and ‘left’ mixed up quite a lot, and there are some serious errors. Contact me if you mean to go this way and I’ll tell you what to watch out for, although I notice that the guide has been revised for 2008 - perhaps some of the errors have been dealt with.

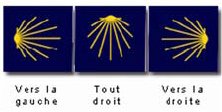

Balisage

It is impossible to navigate by waymarks (balisage) alone. You need three references: the Rando guide, the waymarks, and the 1:100000 map of the area. Make that four – you need to stop and ask for directions quite a bit. You will seldom need the maps, but they are your insurance policy: if you lose the way completely they are your only means of getting back on course. Although the 1:100000 scale sounds big, it is in fact quite adequate for navigation by minor roads. The maps you need are listed in the CSJ guide. I had no problems whatever with the Voie de Tours guide.

Gîte, Labouheyre

My aim was to camp most of the time. In France this is quite feasible. Most settlements of any size have a municipal campsite which is good quality and cheap. Where there is a choice of municipal or private, choose the municipal as the standard of the private sites is somewhat variable and they are more expensive. I also used gîtes and chambres d’hôte (B&B). Compared to the UK the French B&B is a good deal cheaper and of comparable or better quality. The gîtes are excellent. Hotels are cheap, but personally whether in France or UK I prefer B&B. Where breakfast is an optional extra – usually about 6 euros – consider doing without if there is a decent bar nearby. You can do pretty well for six euros in a bar, and it’s a more sociable way to start the day. For food, I usually took a restaurant lunch (three course for 10-15 euros) and then just snacked in the tent at night (baguette, blue cheese, pâté de campagne, beer or tea, leaving enough over for a sandwich next day).

Although camping saves a great deal of money, a tent is of course a weight penalty in your rucksack. At St Palais you can post your tent home (go to the post office and buy one of the postage pre-paid boxes) as from this point onward you can get pilgrim gîtes all the way to the Spanish border. As a rough indicator, travelling through France cost half as much per week as travelling through England. I won’t mention an absolute amount, as I like my creature comforts and spent frightening amounts in bars and restaurants. The food is so-o-o-o-o good.

Les Landes

Forest, Les Landes

Gradignan

Satellite view, Priory of Cayac

You won’t meet many other pilgrims in France, and you will usually have the trail and the gîtes to yourself, at least until you meet the trail from Le Puy at Gibraltar.

It will therefore be a shock when you get to St Jean Pied de Port, and at one blow all privacy is lost and you join the mob. I found it very trying after all the long leagues of tranquil solitude from Dumbarton. Be prepared for this – it’s initially shocking, but you will settle into the new regime in a few days. By the time I got to Santiago I felt quite institutionalised – but I don’t know if that was what I wanted!

At the French/Spanish border

There is already much (too much?) documentation of the Spanish sections of the walk. France is different. Bon courage, pèlerin!